Editor’s Note:

The following is a copy of a paper I wrote in college for a World War II History class. I interviewed my great-uncle, Powell Magee about his experiences as a POW of Japan in the Pacific Theater. With the exception of a few grammar corrections, it is presented here exactly as it was written. I have added multiple photos and maps to help readers understand the story more thoroughly.

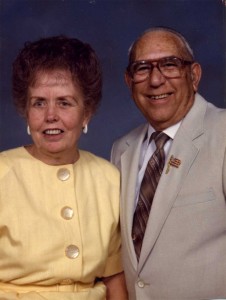

Born March 2, 1920, Powell Magee died as a Child of God, Loving Husband, Beloved Father, Air Force Veteran and United States Hero on July 7, 1995.

This is his story.

A Prisoner of Japan:

A POW’s own story

By: Powell Magee

As told to Paul H. Tarver.

Foreword

The following is the story of Powell Magee’s imprisonment at the hands of the Japanese during World War II. It was taken from a taped interview with Mr. Magee and edited into its present form. I have tried to keep as much of his own words as possible, but to make it more readable and put it into chronological order, some changes were made. The content is still the same. During our interview, it was obvious that even after forty years, some parts of that period were painful to remember; however, one thing that I especially noticed during the interview was Mr. Magee’s repeated use of the phrase, “I was lucky.” Many of his friends were not.

I wish to thank Mr. Magee for allowing me to get his story on paper. I only hope that he feels as good about finally telling it as I did by being honored to hear it. This paper is for him.

Paul H. Tarver

I joined the Air Force in May of 1940 and I left the United States on November 1, 1941, on the ship, S.S. PRESIDENT CLEVELAND. I arrived in Manila on November 18, 1941. That year, Roosevelt had set Thanksgiving up a week, so I got there on Thanksgiving Day. We disembarked from the ship and went to Fort McKinley, just outside of Manila where we were quarantined for fourteen days. We had to stay in tents for the duration of the quarantine, but afterward, we were allowed to do just about anything.., at least until the war broke out. I think I got to go into Manila sometime between the end of the quarantine and the seventh of December. Once the war began, well, that just broke up everything and we began loading ammunition.

I was a Corporal when the war actually began, but sometime during our fighting I was promoted to Private First Class Specialist. They [the government] knew I was married, the new position paid more money. I held that until sometime during my imprisonment, when they gave me a Staff Sergeant rating. Somehow, they got wireless messages out of Corregidor to give us promotions.

I was in the ordnance attached to the 27th Bombardment Group. We handled all the bombs and ammunition for most of the forces on Bataan. The different company trucks would come to our ammo dump, where we would load them up and send them back out. We had six P-.40s that we loaded bombs on, and gradually as the war went on they shipped out to Australia. Once they were all gone, we had less to do, so, we occasionally delivered some of the ammo to the front ourselves.

Most of our work was done out of Cabcaben, but we moved back and forth between there and Manila, that is, until Christmas Eve of ’41. We were at San Marcelino the night of Christmas Eve when we got the word to retreat back down on Bataan. We moved back below to Orion, and stayed there until the Abucay Line fell. Once the line fell, we moved into the Mariveles Mountains where we stayed until we surrendered.

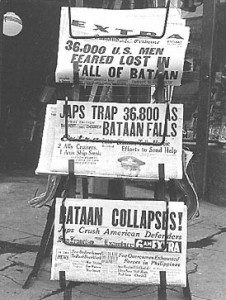

We fought for four months against 300,000 Japanese with about 60,000 men. Our forces consisted of between 17,000 and 20,000 Americans; the rest being Filipino scouts, Filipino army, and Filipino irregulars. Really, we had just about anybody who could shoot a gun.

McArthur left in March, and put Wainwright in charge. At first, it was a real morale boost. We thought that McArthur had gone for help and would be coming back soon with planes, ships, and convoys, it took a while before we began to realize that it would be a long time before he returned. We didn’t think he had just left us there. We thought that sooner or later, he’d come back for us. It was about two weeks before we surrendered when reality began to set in and we understood that it would be a long time before McArthur returned.

We didn’t have anything to defend ourselves with except our rifles, and the Japanese were dropping everything they had on us. They were even dropping old stovepipes with nuts, bolts and pieces of scrap metal inside. The pipes would explode above the ground and scatter the stuff all around and on top of us.

By this time we had been demobilized as an air force unit and absorbed into the infantry. When the second line broke, we retreated into the Mariveles Mountains. This must have been about April 7, because on April 8, we destroyed all of our weapons and shot holes in all the trucks we had. We had been on half rations for about three months and had all of our food was stashed in a cave up in the Mariveles. We blew up the rest of our rations to prevent the Japs from getting and using them. Some of the guys left Bataan and crossed over to Corregidor. I don’t know if it helped them, though. Most of them died later fighting.

On April 9, we marched down out of the mountains and surrendered. We now knew that McArthur wasn’t coming back, because he had told Wainwright to fight to the last man. However, Wainwright said he wasn’t going to do that because he thought that would be inhuman. Wainwright had visited us a few times during the four months we fought to encourage us to hold out. But, once he saw that it was hopeless to fight anymore, he decided to let us take our chances as prisoners.

As soon as we came down out of the mountains with our white flags, the Japanese began hitting and beating us. I was lucky. i didn’t get hit at that time, but a lot of other guys did. They called us all kinds of names…called us Crazy. The Japanese didn’t believe in surrendering. They thought we were dirt. I was really surprised that they even took us as prisoners. The troops we had surrendered to were hardened men. Later on the march, you’d see them pull a man out of the line and never see him again.

We began marching the same day we surrendered. We marched during the daytime, and they would pen us up at night. They had a barbed wire fence (It looked like a cattle lock) that they would pen us up in each night. We marched in columns of four, but you were more or less marching at your own pace. We didn’t have to keep step or anything like that.

There were Artesian wells all along the road, and guys would try to break rank and go get themselves a canteen of water. Sometimes the Japs would shoot and sometime they wouldn’t. If you could catch the right time when a well was close enough to the road, you could run, get a little water, and get back into the same spot. If the guards were spaced a fairly good distance apart, they usually wouldn’t say anything. They couldn’t recognize you anyway so they couldn’t punish you.

Every so often, I don’t remember just how far, or how regularly, they would stop and let us sit down and rest for about five minutes. One particular time we were stopped, a truck came up and a bunch of Japanese officers got out and began jabbering away there among themselves. Finally, they came over to another group of Americans and wanted to know where a particular person was. They finally found him in a gang of us who were marching together. Those officers pulled him out of the line, took a bayonet, cut right around his face, and peeled his face off with him still alive. Then, they stabbed him with the bayonet and killed him. It seems that he had commanded the 31st Infantry (pdf) when the Japanese 10th Marines tried to land behind us on Bataan. He had taken his men and run most of the Japs back into the sea. I don’t know how they found out who he was, but they did and they got rid of him.

I saw them cut a Japanese woman’s breast off because she was trying to give us some food. Other people who gave us food had their tongues cut out. We just wanted to take and get a hold of them jokers and really tear them up. But we knew, it wasn’t any use to do that because we just get killed ourselves.

Some of the guys broke from the ranks and tried to get away. A few of them made it, but most of them didn’t. Early in the morning or late in the afternoon, they would break ranks and head for the woods. Most would wait until we came to a really thick part of the woods and then break. The ones that got away usually joined up with guerilla groups and helped fight their way back down Bataan. I never did try it, I just, I was afraid to try it. Afraid they’d catch me and kill me. I figured I’d stand a better chance by going on and at least I might get a little bit of food. We had no idea that it would be as bad as it was. I guess deep inside we still figured that McArthur was coming back for us, but the further we marched, the less hope we had.

It took us seven days to reach San Fernando and the further we marched up the island the better the treatment got. It still wasn’t good but it was better. See, the further north we marched, the more Japanese Air Force guards we ran into. They still had air supremacy, so they were not too worried about proving themselves as being better than us. In fact, just before we reached San Fernando, they let us go out into a sugar cane field and cut ourselves some stalks. We tied the stalks onto our backs and nibbled on them as we walked. Other than the sugar cane, I only got five tablespoons full of rice on the whole march.

Well, we marched on into San Fernando where we spent the night. This was the only time I remember getting hit on the march. It was the morning after we got there, and somehow, I slept late. I guess I was so exhausted. A Japanese guard came by and hit me with a stick across the leg and woke me up. Then he started jabbering at me, telling me to get up and let’s go, which I did, hurriedly.

They loaded us onto a train that day, and headed for Capas. They stacked us in those railcars like cattle. We couldn’t even sit down. Once we reached Capas, we began marching again, until we reached Camp O’Donnell.

Camp O’Donnell was to be a training base for the Filipino army, before the war. It had barracks and a mess hall. The Japs put us in there any way they could. They didn’t try to keep companies separated or anything, we just were all thrown in there together. Inside our barracks were beds that must have been about three feet high. The mattress was nothing more than bamboo slats laid across the bed. We had no cover, but then we were not in danger of getting cold, because of the hot weather.

I got really bad sick at this camp. I was so weak I didn’t know what to do. Finally, I crawled to the mess hall, and a cook saw me coming. I hadn’t eaten in about ten days, so he took a board he had, it must have been about two feet square, and piled it up with rice and handed it out the door to me. I ate every last bit of it. Sure enough, it stopped my diarrhea and I began to feel better. Two or three days later, the guards asked for a detail to go back down on Bataan. I volunteered for the job because I knew I could get more food if I worked.

Several of us got on a truck and headed back down on Bataan to work in the mechanic’s shop the Japs had set up. They wanted our detail to go out and pull in the trucks that we had shot up before we surrendered on April 9. There were four of us in our particular group and a guard. We had an old van-type truck, and I did most of the driving. We lucked up and got a good guard. A lot of times after we had hooked up to a vehicle and headed out, he would lay his gun down in the back and go to sleep. We could have killed him, I guess, but what good would it have done to kill just one. But, he turned out to be a pretty good Joe.

The Filipinos had little fruit-stands along the roads on Bataan. Usually, on the way back the guard would get us to stop at one of these stands, where he’d buy us candy and bananas. However, I only had this “good” life for about three weeks before I caught malaria.

I couldn’t work anymore, so they sent me to Cabanatuan. It was just outside of San Fernando. It was split into a hospital area and a work area. I stayed in the hospital part for five months. There were different sections in the hospital area itself and as a person got gradually worse and worse, he moved to the next section until he finally died. I don’t remember the total number of men who died at this camp, but I do know that I saw them bury 165 men in one day.

After five months on the hospital side, I finally was able to volunteer for the work side again. I went back to hauling trucks, but shortly thereafter, I got sick again and had to go back to the hospital side.

It was around the middle of ’43 when I finally got a little better. By this time, we all had begun to pick up on a few Japanese terms, but I got lucky. I met up with a guy from Shabuta, MS, named McKee. He had gotten to where he could speak pretty good Japanese. We worked together for a while at Lipa City in the Batangas Province.

We were building an airfield there at Lipa, and the trains would come in bringing the large base rocks for the runway. Well, we had one particular guard that nobody liked. So we did everything we could to get at him. Sometimes we would call him over to show off his muscles and make him lift the rocks until he figured out what was going on. A couple of times we would be up on the train car handing down rocks, and we would do our level best to drop a rock on him. We never hit him, but we made him mad pretty often. One time he got so mad-he picked up a board that was about one inch by ten inches by ten feet long and swung it at us. He wound up hitting a railcar, which only made him madder. He started cursing in Japanese, and finally got so mad that he just turned ‘and walked away. While we worked on the airfield at Lipa City we got all of our information from the Filipino farmers who worked their farms beside the airstrips. We didn’t talk to any of them, but we had ways of getting information. One of the best worked like this:

We had helmets that were made out of halved cocoanut shells. They had a band on the inside. At the end of the day, when all of the men loaded up on the trucks and began to drive off, we made it a point to drop our helmet. We would then beg the driver to go back so we could get it. He usually would and we would continue our journey back to camp. That night we would feel along the inside of that band until we found a small piece of paper. On the paper might be written, “Yankees win 7 to 2.” By that, we knew that the Americans were winning. That kept our morale up pretty good and kept us in touch with the outside world.

Another way to boost morale was to sabotage any and every thing we could. We were building a runway with rocks and dirt. Now if we left holes in the rock base and simply filled it in with dirt, the packer machine would come by and get stuck. It would take them two or three days to get him out of those holes.

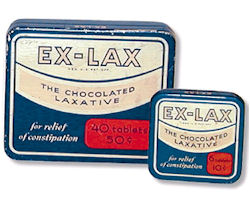

One of the best sabotages that I pulled off involved getting the best of a guard. The Red Cross got some packages in to us in 1943. Now, for some unknown reason they sent each one of us a small box of Ex-Lax. The last thing we needed in the Philippines was a box of Ex-lax. However, for some reason, that morning, I had put my box of Ex-lax in my pocket and headed out to work. Well, this Jap guard saw me and wanted to know what the box was. I told him it was candy and asked him if he wanted it. He looked at it, and I told him to stick it his pocket and to take it home. He did, and I didn’t see him for about three weeks. So, whether that was what caused his absence, I don’t know, but it did give us something to talk about.

After we finished working at that camp, they moved us to the Randolf Field of the Philippines. We named it that because it was sort of like the Randolf Field in San Antonio where they trained all of the pilots. Well, they had a good solid runway, which was built out of a layer of big rocks covered with pea gravel, which was then covered with three to four inches of dirt. But since the Japanese didn’t have anything for us to do, they made us use picks and tear up the runway, clear off the area, and then build the runway back. But, we’d loosen those rocks and then not pack it right. Sabotage. Sure enough, shortly thereafter, late one afternoon, we were in the middle of roll call when we heard the biggest explosion you’ve ever heard. A Japanese fighter plane carrying ammunition had cracked up out there. It had hit a soft spot. Although morale went up drastically, we were punished, too. They lined all of us up and began to hit each of us on the back with a pick handle. I think that’s what’s wrong with my back today. I was lucky; some of the guys got their backs broken.

We stayed at this camp until sometime in 1944 when the Americans began coming back into the area. I remember one day in particular, we were out building revetments for the Japanese airplanes. Revetments were U-shaped embankments 12 to 15 feet high. Planes were backed into them, which protected the planes from shrapnel from bombs dropped by the American planes. Anyway, we were out there working when somebody looked toward Manila, and the sky was just, well, it looked it was full of gnats. It was black; there were so many planes. You could hear bombs bursting and everybody was yelling. We were telling the Japanese that the planes were American Skokies, and they were saying “NO! Japanese Skokie!” Then the planes began to get closer.

In the camp, we had 6 buildings. The Japanese guards lived in the first two and the next three were the prisoners’ barracks and the last one was the mess hail. Across from our barracks was an old plane. But, those American planes came over in droves. They bombed the guards’ barracks and dropped a bomb through the cockpit of that old plane, but never once did they come close to our barracks not the mess hail. Somehow, they knew which barracks were ours, but we still don’t know how they knew. There was only one American casualty that day. One of the bombs kicked up a rock that hit one of our guys in the head. All he got was a scratch.

That night Japanese officers came and told us to pack up. They were moving us to Bilibid prison. They loaded us onto trucks and headed for Manila. Then they took us into Luzon to Bilibid where we stayed for nine days.

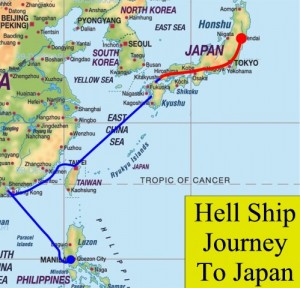

At Bilibid we were fed twice a day. For breakfast, they gave us cracked corn, just like the corn you’d feed to chickens. They gave us about half a can that corn, boiled. Then that night, they gave us about 3/4 of a cup of dry, cooked rice. On the ninth day, they loaded us onto a ship headed for Japan.

They took us to Manila Bay and loaded on the ship and put us in the holds. There was a front and back hold, and they stuffed 1,122 of us down into those two holds, we couldn’t sit down. There were about 500 of us in one hold and 600 in the other. We stayed on that boat for thirty-nine days.

We set sail from Manila Bay and moved up the coast of China. Everybody got to working together and finally maneuvered ourselves into sitting positions. On the inside of the ship there were ribs running up and down the sides of the holds. They were fairly wide and they had boards going crossways. Some of us climbed up onto those boards and rode there for most of the trip.

According to Japanese figures, of the 50,000 POWs they shipped, 10,800 died at sea. Going by Allied figures, more Americans died in the sinking of the Arisan Maru than died in the weeks of the death march out of Bataan, or in the months at Camp O’Donnell, which were the two worst sustained atrocities committed by the Japanese against Americans. More Dutchmen died in the sinking of the Jun’yo Maru than in a year on the Burma-Siam railroad. The total deaths of all nationalities on the railroad added up to the war’s biggest sustained Japanese atrocity against Allied POWs. Total deaths of all nationalities at sea were second in number only to total deaths on the railroad. Of all POWs who died in the Pacific war, one in every three was killed on the water by friendly fire.

— Gavan Daws, Prisoners of the Japanese

I had been down in the hold for maybe, 12 or 15 days when I finally decided to get up onto the wall. It was just getting so bad down on the bottom. It was terrible. Guys began drinking their own urine or seawater because there was nothing else to drink. I got lucky and got sick so the guards let me come up on the deck. While I was up on deck, I helped some of the other sick guys, and quickly gained my strength back. I guess I got well too fast, because it wasn’t long before the Japs realized I was feeling better and put me back into the hold.

We proceeded to Hong Kong Harbor and got trapped by some U.S. submarines. We had to go up the Canton River at night to keep submarines from slipping in and sinking us. American planes constantly bombed, but it always seemed that they hit on each side of us and miss. After being trapped for 11 days in the Harbor, we pulled out and headed for Formosa.

We stayed at a camp at Taipei for about 2 months. We had to work there too, but it was fairly easy. We had to go out between 8 and 9 in the morning and hoe in some gardens they had around the camp. We had an interpreter there who had graduated from UCLA, so we didn’t have too much language problem. The Japanese treated us pretty good there on Formosa. In fact, for the Christmas of ’44, they kill 600 rabbits and stewed them up for us. That’s about the only good thing they did for us. After staying at Taipei for two months we got on another boat and left Formosa for Kyushu Island. It took fourteen days to get there.

We landed on Kyushu in January of 1945 and got on a train to cross the island. We crossed over from Kyushu to Honshu Island [Japan’s main island] on ferryboat. Then we got on yet another train and began the trip up the coast of Japan. The further north we moved the more snow we saw, and by the time we got to Sendai, it was strictly snow. It was or must have been five or six feet deep up there. We got off the train at Sendai and walked about five or six miles into the mountains to the camp we stayed at until the war ended.

During the spring of 1945, we worked at the camp in Sendai. We could do very little work because of the snow, but since trucks could not get up the mountain, it was our duty to go into town and unload the supply train whenever it came in. We ate better because we were able to steal food from the bags as we brought them up the mountain.

We wore old World War One uniform pants, the kind with the leg wrappings. We would make a hole in a bag of rice and let the rice fall into our pants. The rice would work its way down to the legs of our pants, and since we were never searched, we could get past the guards. Our guard knew we were taking the food, but he told us if we got caught he’d say he didn’t know us.

The food they gave us was a little better, too. It had to be since the work we were doing then was harder. We had more fish and dog while we were at Sendai. The fish was a frozen fish that the cooks cleaned for us. We also ate a lot of dog while we were in Japan. If I had been a rat, I would have stayed as far away as possible from any of the camps. I didn’t eat any rats, but many people did.

Around May of ’45, the work began to get harder. We worked in the lead and zinc mines gathering ore for the Japanese war machine. We had ten men details to go into the mines and load the ore onto small railcars. The cars were much smaller, because of the weight of the ore.

Anyway, I didn’t have to work in the mines much because of a particular incident. I had to go into the mine and work one day, and as the ore was broken loose from the walls, I was loading it onto the small railcars. The rails the cars rode on were built on a small incline that made it easy to roll them out of the mines. After loading a car, I was going to ride the car out of the mine. As I rode, the car went faster and faster. Finally, I decided that it was going too fast for me and tried to jump off. However, by this time, I was moving entirely too fast and was afraid to jump. I started yelling, “Get Out of the Way!” I must have been making 45 or 50 miles per hour when I came out of the end of that mine. When it finally stopped, the guards were furious. One of them took a big hand rod that the men used to drill holes in the rocks, and swung it at me. I ducked and he hit the edge of the tunnel with the rod. It almost shook his teeth out. They really raised Cain about it, but after they cooled down and found out what happened, they didn’t say too much. But, that was the only time I had to work in the mine from then on.

I was lucky. It was cold and damp down in there. And, it was easy to get lead poisoning in those mines. One guy got lead poisoning and they had to amputate his leg at his knee. He said in normal times his weight usually was 218 to 220. He weighed 98 pounds before he died. The lead poisoning just finally went all over his body.

Finally, it was all over. Well, at least the imprisonment. They [the US] had dropped The Bomb. The old Jap commander at the camp came out the day after they dropped the bomb around 2:00 pm, to tell us that the war was over. There was some kind of yelling and crying going on.

The guards got scared that we would take our revenge on them, so they ran off shortly after the commander came out. Only three Japanese stayed that night; the commander, his interpreter, and one other guy. We went looking that night for the guards that had run of f, but we didn’t find any of them.

The next day, two fighter pilots flew over and dropped leaflets telling us that supplies were on the way. However, those fighters missed our camp and all of the leaflets fell in the city down below us. Later that afternoon, two big bombers flew over our camp real low, made a big circle, and then the bomb-doors began to open. The first thing we’ thought was, “Oh, my God, don’t tell me that the Americans are gonna bomb us, since the war has ended. Since we didn’t know that they were dropping food and clothing, we began to run to get away. Two guys, who were running, were killed by big tubes of clothes. I guess that was about the worst thing I saw over there. These two guys had made it through all the torture and were killed accidentally by their own side.

We gathered all the food up and took it to the mess hall and had a feast that night. At midnight, we had a feast. Then, we got word that there was to be another drop in about two days. Well, we did this one right. We went outside the camp and made big targets out of a bunch of sheets. This time, it felt really good to see them planes coming over, even with the bomb bay doors open.

We were told to stay at the camp until officers came and got us. Once they came, we went to Tokyo Harbor, where we spent the night on the Battleship Missouri. Within a few days, we were on our way back home.

We left San Francisco on November 1, 1941, and returned on October 26, 1945. We lacked just a few days being overseas four years. I was discharged on May 31, 1946. I had enlisted on May 23, 1940. Out of the six years, I had spent three and one half years as a prisoner of Japan.

I called my wife, Inez, from San Francisco and talked to her for the first time in five years. In fact, she had not heard from me that whole time. She didn’t even know if I was alive, until I got back. I cried over the phone with her. It felt good to be back home.

I suppose that during my stay the worst part had to be the not knowing whether I’d be alive tomorrow. Whether your own planes would drop the bomb that would kill you. We didn’t know whether those Japs would go berserk tomorrow and kill the whole lot of us like cattle. We just couldn’t envision a small country like Japan taking over America, but since we didn’t know if they had or not all we could do was hope that they hadn’t. You didn’t know what was going to become of you next.

You just didn’t know.

GuruGraffiti Writing On The Walls Of The Internet

GuruGraffiti Writing On The Walls Of The Internet

Wow, what a story, what a great man.

I am a veteran of the US Army. I didnt really see any action while I was in the Army but I was in Saudi Arabia for part of it. This story makes me more proud to have served my country. Your uncle is truly an American Hero. I am so glad that I came across this story. I would like to print this story out if you dont mind to read when ever I need to feel a little more patriotic. I have been having a rough time and dont feel very patriotic anymore. I would still go and fight for our country if ask and be willing to die for it (as so many of your uncle’s friends and fellow servicemen did.) I had to say thank you for making me feel proud to be an American.

Wow, where do I began. When my grandfather passed away over 15 years ago I was given a manuscript of him giving an interview about his time as a P.O.W. with a man name Paul is all I knew till yesterday. Over the years I kept this manuscript close and once a year or so I would look over it, read it. I always wanted to share my grandfather’s words from this manuscript which tells a story of what he went through as a P.O.W. in WWII because my grandfather spoke to me that one day he would like to tell his story and have other people read about it.

So here I am last night and decided to do a little research and print up pictures and maps and use this manuscript that was done by a man named paul and put it together for my father for Father’s day, of course the interview was already done and what a story it was and what an interview. My plan was just to re-type it exactly like it was due to my copy was pretty old and beat up from the years and give it to my father due to he has never read this.

Something hit me and said just google my grandfathers name, Powell Magee, and what a blessing of a surprise here is a story about my grandfather pops up on the screen, my grandfather I couldn’t believe it and the writer was a Paul Tarver. I had goose bumps going through me and after I began to read it was the same 100% facts and story from the manuscript I kept so many years and the writer was the same person that interviewed my grandfather, WOW.

I called paul the very next day and come to find out we are related.

On behalf of the Magee family and myself I want to personally Thank Paul for after years to take the time and Honor my grandfather by telling his story was a true gift of respect and Honor. For me to see that Paul created a website and shared this story and you can google my grandfather and read his story is something I will be always grateful. I know that my grandpa is up in Heaven looking down with a smile that his story was finally told. This will be a great fathers day gift to my dad when I tell him of how Paul Tarver Honored is father by sharing with the world my Grandfather,Powell Magee’s words and story from an interview that was done many many years ago.

Thank you again Paul,

Chris Magee

Chris,

Thank you for the kind comments and I am so pleased that you are happy with the results. This story was posted in 2009 in preparation for a radio show that I do every year at Memorial Day and I thought you might like to listen to the show to hear my description of the unveiling of Powell Magee’s story. You can listen to all four parts of the show by clicking on the link below:

WMOX Memorial Day Show – 2009

Thanks again! It was great to reconnect with some of the family and I hope your Dad has a wonderful Father’s Day!

My grandfather, Colonel Frank Brezina was the Quartermaster at the time of the fall of Corregidor. There is a passage in a book where he reported the amount of rice and coffee which was left to sustain the troops before the surrender. He survived the Death March, but later succumbed to disease in Shirakawa POW camp in what now is Taiwan. I have been trying to find information about him, but have pretty much been unsuccessful. He was in the POW camp with General Wainwright, and when Colonel Brezina died, there was a Masonic Ritual for him. If anyone has any information about Col. Brezina, I would appreciate it.

Paul, I’m so glad that you took the time to interview and write up your uncle’s story. My book has been published, Never Give Up, as told by Drolan Chandler, to Myra Jones. Like you, I tried to keep it as much like he talked as possible. I hope your readers will look it up because his determination to survive is very inspiring. His feisty attitude got him into several dangerous and, yes, humorous situations. I included 200+ photographs and a dozen maps, to help readers visualize the places, including Bilibid, O’Donnell, and Cabanatuan in the Philippines, the hell ship he was transferred to Japan on, Clyde Maru, and Camp #17 in Omuta, where he worked in the unsafe coal mines. The book is available at Amazon and other popular sites, as well as at my BookShop page at Bookbaby publisher (see website below) which gives an Overview, Description, Author Profile, and you can read a sample chapter. Use coupon code 9VPUZ8 for a $2.99 discount. I hope you’ll read his amazing story!

Editor’s note: The book is available for purchase at BookBaby.com and Amazon.com

Thanks – I picked the book up on Amazon. I had a great uncle at Camp O’Donnell and survived until 1944, but (from what I can gather) was basically worked to death. I look forward to reading your book and getting more information.

Thank you for this – I like reading info on the Bataan POW’s. So tragic, but that Ex Lax sabotage was dang good.